Executive Summary

The Portuguese Republic has entered a period of unprecedented institutional tension following the first round of the 2026 presidential election. For only the second time in the five decades since the restoration of democracy, the country will proceed to a second-round run-off on 8 February.

The results from 18 January have crystallised a fragmented political landscape. Moderate socialist and former party leader António José Seguro leads with 31.1 per cent, followed by André Ventura, leader of the populist right-wing party Chega, with 23.5 per cent. With the elimination of the centre-right and liberal candidates, the forthcoming vote has become a de facto referendum on Portugal’s role within the European Union and on its domestic constitutional stability.

The failure of the centre-right candidate, Luís Marques Mendes, who finished with just 11 per cent, represents a historic collapse for the governing Social Democratic Party (PSD) in a presidential contest.

This outcome has left Prime Minister Luís Montenegro’s minority government in a strategic vacuum, given that the presidency holds the authority to dissolve parliament and veto legislation. The result of the run-off will determine whether the executive faces a cooperative constitutional moderator or a disruptive antagonist capable of precipitating a collapse of the current administration.

How will the candidates influence domestic stability?

António José Seguro has built his campaign around the concept of active stability and institutional security. He has successfully unified a fragmented left and is now appealing to moderate right-wing voters seeking to block the far right. Seguro has framed the run-off as a choice between democracy and disruption, arguing that left-wing voters have demonstrated greater prudence than party leaders who attempted to balkanise the campaign.

A Seguro victory would likely usher in a period of cohabitation with the Montenegro government. In this scenario, the president would function as a constitutional filter, using veto powers to ensure that government policies, particularly on labour law and social benefits, do not alienate the social majority.

André Ventura, by contrast, views the presidency as a platform for radical systemic change. Since the first-round results, he has remained openly combative, stating that he will fight “day by day and second by second” to prevent a socialist presidency. Ventura has pledged that, if elected, he will use his constitutional powers to force a new legislative election should the government refuse to include Chega in a formal coalition.

He has framed his candidacy as a struggle against corruption and uncontrolled immigration, arguing that Portugal requires a disruptive alternative to shake up the political system. A Ventura victory would likely result in immediate institutional deadlock and could trigger a constitutional crisis if he seeks to use the presidential power of dissolution to override the existing parliamentary majority.

What are the implications for the European Union?

The outcome of the 8 February run-off will serve as a barometer for the resilience of Europe’s political centre in the face of rising national populism. A victory for António José Seguro would be welcomed in Brussels as a signal of continuity and reliability.

Seguro has emphasised the importance of international stability, noting that minority governments are inherently subject to competing political pressures and that such fragility is especially dangerous in a world increasingly shaped by autocratic actors. Under a Seguro presidency, Portugal would likely remain a staunch supporter of Eurozone fiscal rules and a committed participant in the European Union’s push towards deeper military and economic integration.

A Ventura presidency would mark the definitive end of the so-called Iberian exception and align Portugal with the sovereigntist bloc within the European Council. This would likely introducenew sources of friction within the Union, as Ventura has expressed scepticism towards Brussels-imposed policies on migration and border management.

His approach would mirror national-populist shifts seen elsewhere in the EU, potentially complicating consensus on issues ranging from the common budget to the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. For the European Commission, the central risk is that a traditionally pro-integrationist member state becomes a disruptive actor prioritising domestic nationalist interests over regional cooperation.

What does this mean for the Lusophone world and beyond?

Portugal has historically used its soft power to act as a bridge between the European Union and the Lusophone (Portugueses-speaking) world, particularly Brazil and its former African colonies. António José Seguro intends to preserve this role, advocating a multilateral approach that safeguards the mobility agreements and cultural exchanges underpinning the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP).

He regards these relationships as integral to Portugal’s strategic relevance on the global stage. A Seguro presidency would ensure that Lisbon remains a predictable and credible intermediary in the Global South, particularly as the European Union seeks to counter the growing influence of rival powers in Africa and South America.

The rhetoric of André Ventura poses a direct challenge to this longstanding foreign policy pillar. His focus on uncontrolled immigration and calls for stricter residency requirements have already generated diplomatic friction, especially with Brazil. Ventura has called for an end to what he describes as a subsidy-ridden state and has portrayed existing immigration laws as emblematic of political failure.

If implemented, his nationalist agenda could alienate traditional Lusophone partners and erode Portugal’s role as a diplomatic facilitator. Such an inward turn would likely be interpreted by other global powers as an opportunity to fill the resulting vacuum in trade and infrastructure engagement across the Lusophone world.

Strategic Outlook

The run-off on 8 February will determine Portugal’s institutional trajectory for the next five years. B&K assesses that, while António José Seguro remains the favourite due to Ventura’s high rejection rate among the broader electorate, the contest is likely to be the closest presidential election in Portuguese history.

This reflects the transformation of the populist right from a protest phenomenon into a permanent and influential component of the political system. Even in defeat, Ventura’s performance is likely to pressure the centre-right government into adopting tougher positions on migration and security to placate a disaffected segment of its base.

At this stage, the most probable outcome remains a Seguro victory followed by a period of negotiated stability. In this scenario, the presidency would act as a constraint on the Montenegro administration, ensuring adherence to a moderate governing consensus.

However, this stability would come at the cost of slower legislative progress and a more contested political environment. International observers should prepare for a Portugal that is increasingly inward-looking and where traditional bipartisanship has given way to a complex, multipolar system requiring continual tactical adjustment. The coming three weeks will represent a decisive test of Portugal’s institutional resilience amid deepening social and political polarisation.

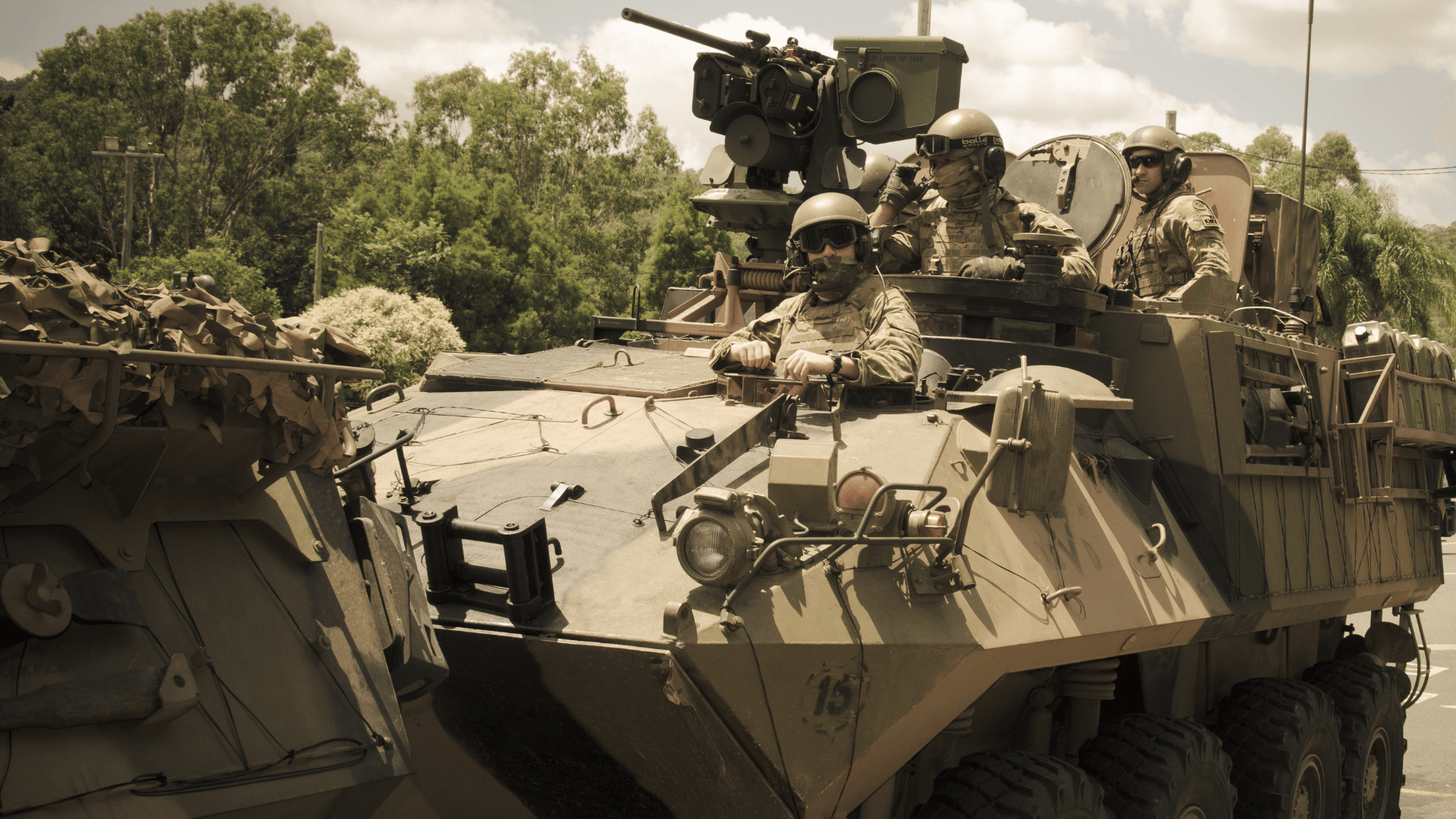

Cover photo: Official Instagram account of António José Seguro, a candidate for the 2026 presidential election in Portugal