Executive Summary

At Davos 2026, China avoided overt confrontation and instead deployed a strategy of calculated restraint, positioning itself as a predictable and non-combative interlocuteur amid visible Western tensions. This posture may have created the appearance of quiet advantage, but did not translate into a substantive diplomatic or strategic win.

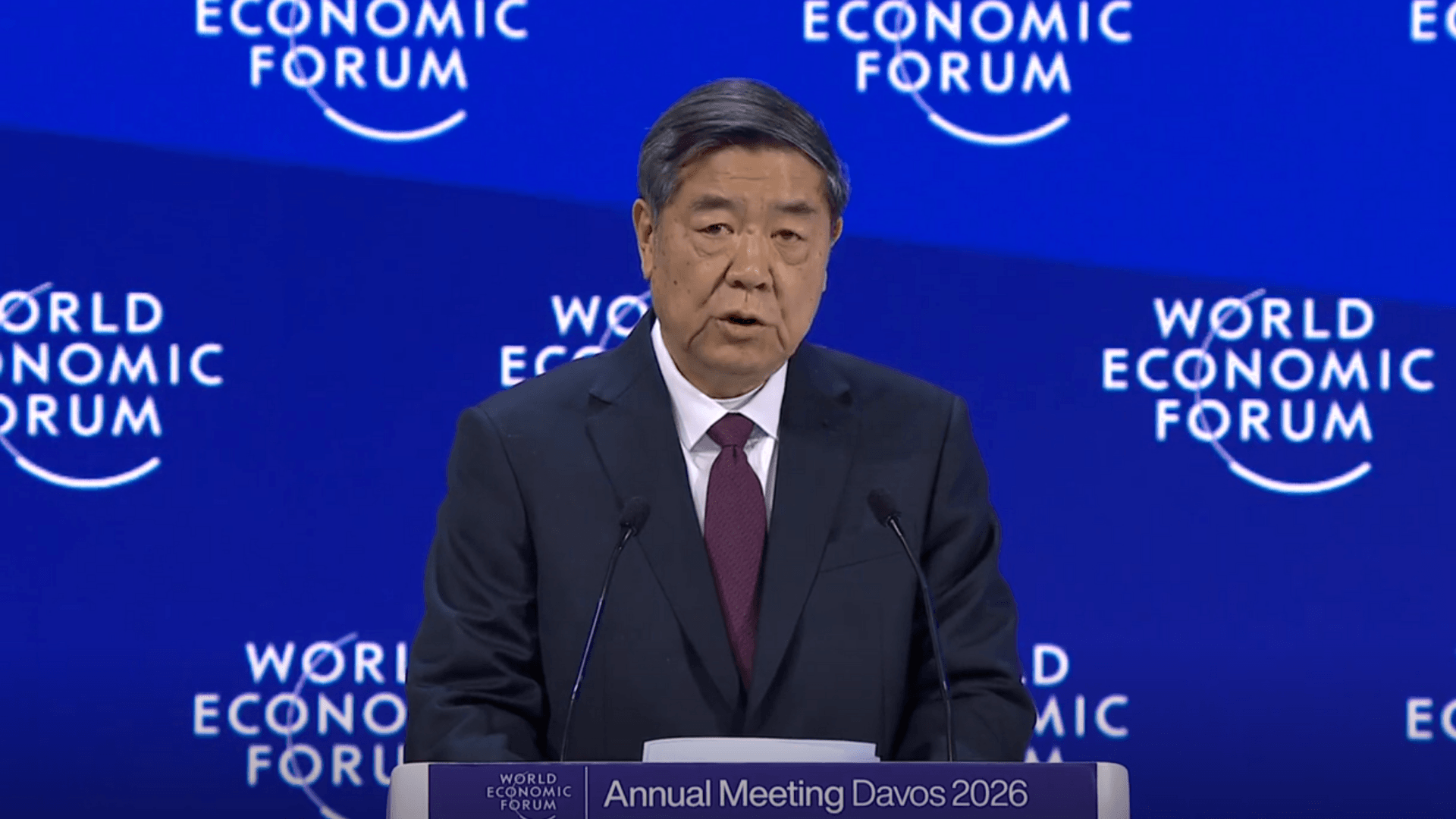

Beijing largely reiterated long-standing talking points on openness, multilateralism, and supply-chain continuity, without announcing new commitments, initiatives, or alignments, and crucially without elevating the forum through the presence of Xi Jinping himself – sending lower-ranking Vice-Premier He Lifeng in lieu of Xi.

Parallel Chinese state media framing sought to portray Western division as a source of legitimacy transfer, yet this narrative ran ahead of what was actually delivered on the ground, where signals of realignment away from the United States remained limited and highly qualified.

Managerial Diplomacy

The 56th Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos served as a revealing test of China’s global positioning rather than a decisive inflection point. Moving away from the high-stakes friction that defined previous years, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) executed a strategy of calculated restraint.

However, restraint in this context functioned more as risk management than as strategic advance. By presenting itself as a source of continuity amidst a global landscape of tariff shocks and policy volatility, Beijing contrasted itself rhetorically with Washington, but stopped short of converting this contrast into leadership or agenda-setting power.

The centrepiece of China’s presence at Davos was the address by Vice-Premier He Lifeng, which framed the country not as a challenger to the global system, but as its primary economic ballast. The speech was notable for its managerial tone, emphasising “openness,” “multilateralism,” and the “stability of global supply chains.”

Yet these themes closely mirrored China’s established Davos messaging from previous years and did not signal a policy shift or new offer to Europe or middle powers. Unlike earlier moments when Beijing used Davos to unveil major initiatives or recalibrate its external posture, this year’s intervention was deliberately modest in both ambition and scope.

The absence of Xi Jinping was itself a signal. By delegating to He Lifeng, Beijing avoided elevating Davos into a forum of strategic consequence, reinforcing the impression that China sought to benefit passively from Western tensions rather than actively reshape the global order. In contrast to periods when China has used high-level presence to project confidence and inevitability, the leadership choice suggested caution and message discipline rather than momentum.

Limited Signals of Alignment

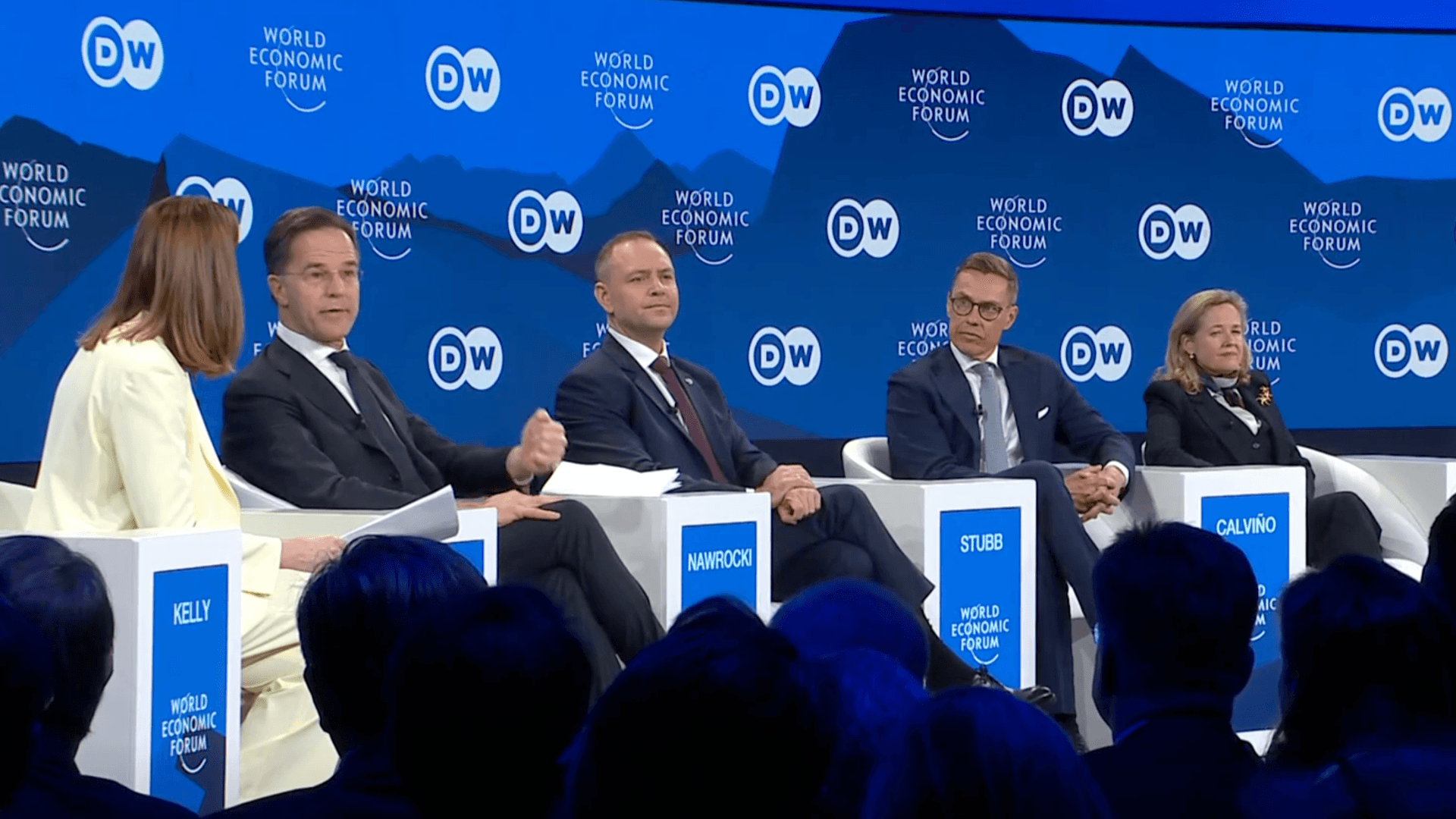

This diplomatic “stillness” has been described by some participants as a means of allowing Western divisions to play out organically. The evidence from Davos, however, points to hedging – not peeling-away. While leaders expressed frustration with U.S. trade policy and political volatility, these expressions did not coalesce into a broader or coordinated shift toward China.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s intervention attracted outsized attention. Carney’s description of China as a “reliable and predictable partner,” coupled with his criticism of tariff weaponisation and “American hegemony,” was notable. It also comes soon after Canada and China inked a “New Strategic Partnership” to slash Canadian tariffs on Chinese electronic vehicles to 6.1%, and a reciprocal drop of Chinese tarrifs on Canadian canola.

However, this positioning reflected Canada’s long-standing preference for multilateral economic stability rather than a decisive strategic pivot toward Beijing. Carney did not announce new bilateral frameworks, security cooperation, or industrial integration with China, and his remarks remained framed within the context of risk diversification rather than alignment substitution.

Similarly, French President Emmanuel Macron’s comments underscored European frustration with U.S. unpredictability, but stopped well short of endorsing China as an alternative anchor. European actors at Davos continued to emphasise autonomy, de-risking, and selective engagement – concepts fundamentally at odds with the notion of a wholesale pivot toward Beijing.

Narratives Without Commitment

The forum also highlighted divergence in narratives surrounding the energy transition. While U.S. representatives criticised EU net-zero ambitions and advocated for a renewed focus on hydrocarbons, China reaffirmed its commitment to green technologies. By framing its dominance in solar, wind, and EV technologies as a contribution to “global public goods,” Beijing appealed rhetorically to European audiences.

This appeal did not resolve underlying tensions over overcapacity, subsidies, and market distortion. China’s continued export of manufacturing overcapacity – particularly in the electric vehicle sector – remains a structural concern with no immediate solution. This reality undercut Beijing’s stabiliser narrative and reinforced European caution rather than trust.

State Media Framing Versus Forum Reality

Chinese state media coverage of Davos 2026 explicitly framed Western division as an enabling condition for China’s rise in credibility, recasting the forum through a legitimacy-transfer lens. Outlets such as the Global Times emphasised contrasts between He Lifeng’s language of multilateralism and what they described as U.S.-driven uncertainty rooted in tariffs, alliance friction, and personalised diplomacy.

This framing was more assertive than the reality it described. While Western anxiety was visible, it did not automatically convert into confidence in China. The argument that legitimacy is shifting from rhetoric to performance was prominent in state media narratives, yet European and middle-power actors continued to judge China primarily through the lens of implementation risks, regulatory asymmetries, and strategic dependency concerns.

An article published by the Belt and Road News Network (BRNN) on January 21 embedded Davos within a broader narrative of structural divergence between U.S. unilateralism and China’s development-centred globalisation. It contrasted U.S. tariffs and downgraded growth forecasts with China’s Belt and Road projects, tariff reductions for developing countries, and institutional openings such as the Hainan Free Trade Port. However, these examples largely reiterated existing policy lines rather than reflecting new commitments catalysed by Davos itself.

Concluding Assessment

A more sober reading of Davos 2026 is that China succeeded in not losing, rather than in winning. By emphasising predictability, continuity, and managerial competence, Beijing avoided becoming a focal point of controversy and benefited from visible Western tensions. Yet it did not capitalise on those tensions to reposition itself as a substitute leader or to secure concrete strategic gains.

The absence of Xi Jinping, the lack of new policy announcements, and the limited scope of alignment signals from Western leaders all point to a constrained outcome. China allowed contrast to emerge through restraint, but contrast alone did not produce conversion. Davos revealed a world uneasy with U.S. volatility, but not one ready to re-anchor itself in Beijing.

Image source: World Economic Forum (He Lifeng, Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic of China)