The current diplomatic friction between the United States, the Kingdom of Denmark, and the European Union regarding the status of Greenland represents a significant shift in Arctic governance and transatlantic relations.

For B&K Agency stakeholders, this situation requires an objective understanding of the underlying strategic motivations and the structural changes occurring within the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).

The issue has evolved from a matter of bilateral real estate interest into a complex multilateral dispute involving trade policy, resource security, and the legal definition of sovereign integrity within a shared security alliance.

In this Strategic Assessment, B&K Agency’s Geopolitical Intelligence Team examines the move toward a more transactional model of diplomacy and its implications for the European Union’s long-term strategic positioning between the United States and other global powers.

Why Does the USA Want Greenland?

The renewed US interest in Greenland, formalised in early 2026, is rooted in a fundamental reassessment of the Arctic as a theatre of great power competition. From the perspective of Washington, Greenland occupies a central position in the GIUK (Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom) gap, a naval chokepoint that is essential for monitoring Russian northern fleet activity and managing the increasing presence of Chinese commercial vessels in the High North.

The US administration views direct administrative or sovereign control over Greenland as a means to streamline the expansion of the Thule Air Base and to establish a permanent maritime presence that is less dependent on the shifting political climate in Copenhagen. This is framed by Washington as a necessary corrective to decades of European “under-investment” in Arctic security. President Trump has explicitly argued that the EU’s failure to meet its 2 per cent GDP defence spending targets has left Greenland’s vast coastline vulnerable, necessitating a US takeover to prevent a strategic vacuum.

The secondary driver of this policy is the global competition for critical raw materials. Greenland contains substantial deposits of rare earth elements, which are vital for the manufacturing of semiconductors, electric vehicle batteries, and advanced guidance systems. Currently, the global supply chain for these minerals is heavily concentrated in China. US policymakers argue that securing these reserves through a direct territorial arrangement would ensure the long-term resilience of the American and allied industrial bases.

The third driver of the USA’s push for Greenland is the “Golden Dome” initiative, a multi-layered space-based missile defence system that the Trump administration views as an absolute necessity for 21st-century deterrence. Unlike traditional mid-course interceptors, the “Golden Dome” seeks to achieve a “boost-phase” intercept ability, which requires sensors and kinetic kill vehicles to be positioned in the cosmos directly along the flight paths of adversary missiles. Greenland’s unique high-latitude geography provides an ideal platform for these orbital tracking stations and interceptors, allowing the US to potentially neutralise ballistic and hypersonic threats before they leave the upper atmosphere.

To facilitate this, the US has introduced a series of economic measures, including proposed tariff adjustments under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, intended to incentivise a negotiated settlement regarding the island’s status. These measures are presented as a tool of economic statecraft to align the strategic geography of the Arctic with the resource requirements of the 21st century.

The EU Rallies Around Danish Sovereignty

The European Union and the Danish government have responded to these developments by reinforcing the legal and political sanctity of the current territorial status quo. For Denmark, the issue is one of constitutional law and the self-determination of the Greenlandic people. The Greenlandic government in Nuuk has consistently expressed a desire for increased autonomy or eventual independence, but within a framework of cooperation with Copenhagen rather than a transfer of administration to a third party.

The EU has aligned itself with Denmark, viewing the US approach as a challenge to the rules-based international order that has governed the continent since 1945. This has led to the activation of the EU’s Anti-Coercion Instrument, a technical mechanism designed to provide a proportionate economic response to external pressures on the sovereign decisions of member states. In a direct escalatory move, the European Commission is currently readying a €93 billion package of retaliatory tariffs targeting high-value US exports, including: automobiles, aircraft parts, and industrial machinery – scheduled to trigger if the US proceeds with its February 1st levies.

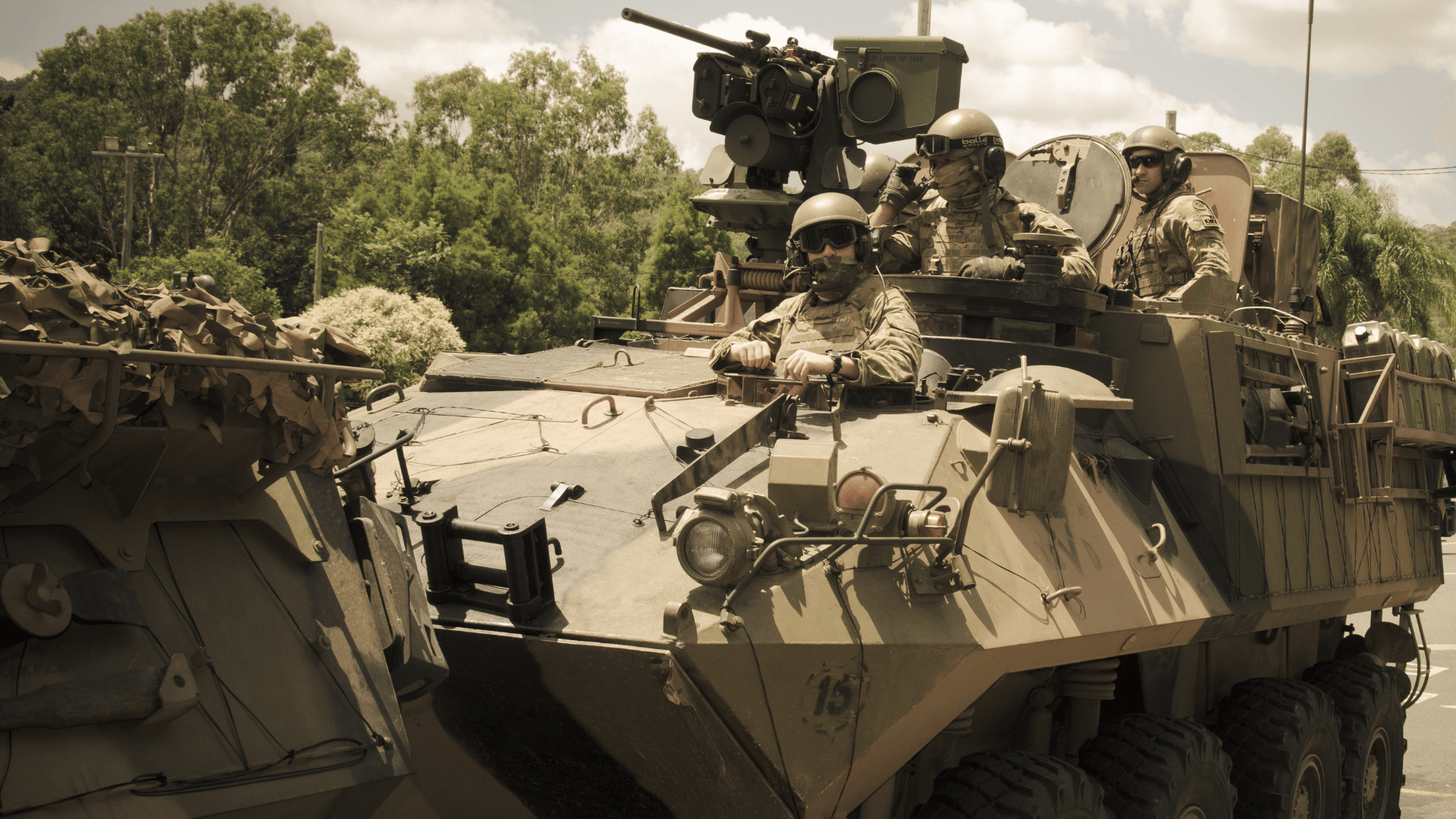

The deployment of personnel under Operation Arctic Endurance is another key component of this response. Rather than being a conventional military escalation, the mission is designed as a collective policing and sovereignty-support operation. It includes contributions from several EU member states and the United Kingdom, intended to demonstrate that the defence of Greenlandic territory is a shared European responsibility.

This collective stance has created a unique friction point within NATO. While all parties remain formal allies, the disagreement over Greenland’s status has forced a technical decoupling of Arctic security planning. European capitals are increasingly discussing the need for a European pillar within NATO that can operate with greater autonomy if the strategic priorities of the United States diverge significantly from those of its European partners.

Arctic Realignment

One of the most significant consequences of the USA-Greenland-EU issue is the potential for a fundamental realignment of the European Union’s global strategy. While the EU had traditionally sought to maintain a balanced relationship with the United States as its primary security partner and China as a major economic partner, the EU has since shifted its posture towards a more assertive strategic autonomy. However, given the broader trade volatility established by the Trump administration’s announcement of universal baseline tariffs in April 2025, the January 2026 announcement of a 10 per cent tariff on several European allies almost pushed the EU to consider retaliatory trade bazooka.

If the US continues to utilise trade tariffs as a primary tool for territorial or strategic negotiations, the EU may seek to de-risk its economy by diversifying its partnerships. This could involve playing off the interests of the United States against those of China and other emerging powers to ensure that European trade remains insulated from transatlantic political disputes.

This shift would have a profound impact on Arctic governance. China, which defines itself as a “near-Arctic state,” has observed the friction within the Western alliance with keen interest. Beijing has historically sought to increase its footprint in Greenland through mining investments and infrastructure projects, many of which were previously blocked due to US security concerns.

However, if the relationship between the EU and the US remains strained, the Greenlandic government might find itself in a position to leverage interest from Chinese state-owned enterprises to gain better terms from both Washington and Brussels. This creates a multi-polar competition for influence on the island, where the local government in Nuuk could theoretically auction development rights to the highest bidder, regardless of traditional Cold War-era alliances. Under the 2009 Act on Greenland Self-Government, the local administration (Naalakkersuisut) possesses full legislative and executive authority over its mineral resources and subsoil rights, providing it with the legal agency to conclude such agreements – unless the Danish government invokes its contested national security veto.

What Russia Stands to Gain

For Russia, the deepening Greenland crisis offers an opportune development in its strategic deadlock of the war in Ukraine. Moscow’s approach to the showdown over Greenland is to troll NATO and hope its unity falls apart under the pressure of transactional diplomacy. While President Trump has cited the Russian threat as the primary reason for acquiring Greenland, the Kremlin has reacted with a disorienting mix of feigned sympathy for Greenlandic residents, and open encouragement for Trump’s ambitions.

The near break-up of NATO over Greenland would have distracted Western capitals, potentially weakening the political resolve needed to sustain high-intensity military aid to Ukraine. This distraction has already paid dividends for Moscow, as European leaders scambled to Davos in January 2026 to defuse the Greenland situation, the high-level signing of the $800 billion “Prosperity Plan” for Ukraine’s reconstruction has been postponed, allowing the conflict to assume a lower priority on the EU agenda.

The strategic acquisition of Greenland would fundamentally alter Russia’s nuclear calculus, especially regarding its new Oreshnik (Hazel) missiles. The Oreshniks are nuclear-capable, hypersonic intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs), which reached a terminal speed of Mach 11 during strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure in late 2025. The missiles are designed to overwhelm existing European air defences through a multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) payload. However, a fully operational “Golden Dome” based in Greenland would grant the US the ability to tarck and intercept the Oreshnik warheads in the cosmos, before they can deploy their submunitions over Allied territory.

The establishment of an American-sovereign Greenland forces the Russian General Staff to undergo a total strategic reassessment of their military asset organisation. With their primary Atlantic exit through the GIUK Gap under direct US sovereign monitoring and the virtually unstoppable hypersonic deterrent negated by the “Golden Dome,” Moscow may be compelled to withdraw its Northern Fleet assets deeper into the Arctic bastion and redirect massive funding away from conventional forces towards experimental, space-symmetric countermeasures to maintain any semblance of global parity.

The Future of NATO and the Rules-Based Order

The Greenland dispute serves as a case study for the evolving nature of 21st-century alliances. The situation suggests that the traditional “one for all and all for one” logic of Article 5 is being tested by internal transactional demands. While the US maintains that its interest in Greenland is for the benefit of the entire alliance’s security, the methods employed have led to a crisis of confidence.

The B&K Agency Geopolitical Intelligence Team underscores that the primary takeaway in this dispute is the fragmentation of the Western consensus. The Arctic is no longer a zone of “high latitude, low tension” but has become a primary site for the testing of new diplomatic and economic pressures. This environment favours states and actors who can navigate a world of shifting, issue-specific coalitions rather than fixed, permanent blocks.

Furthermore, the dispute highlights the limits of international law in the face of strategic necessity. The US position suggests that the existing legal frameworks for territorial acquisition and maritime rights may be insufficient to address the speed of environmental change in the North.

Conversely, the EU’s insistence on a strict adherence to sovereign norms reflects a desire to prevent the return of a “spheres of influence” model of global politics. The resolution of the Greenland issue will likely set the precedent for how other contested regions, such as the South China Sea or the Antarctic, are managed in an era of resource scarcity and climate instability.

The Future of Greenland

The Davos meeting proved effective for the US-EU dialogue. On 21 January, President Trump announced that the framework for a deal concerning Greenland and the entire Arctic region is in the works. Considering the concerted push by the Trump administration and the active negotiations by the EU, the USA-Greenland-EU issue may be resolved in the very near term. Any imminent deal would likely bypass a total purchase in favour of an expanded security compact that grants the United States broader military and jurisdictional access to Greenlandic soil for its “Golden Dome” missile defence system.

One thing is clear: the EU is being pushed to increase their defence capabilities once again. The Union will likely continue to strengthen its security architecture and trade defence instruments, while the US will likely maintain its focus on the Arctic as a core component of its national security perimeter. This creates a dual-track reality for global markets: a high degree of integration in traditional sectors, contrasted with intense competition and potential decoupling in strategic areas such as Arctic logistics and critical mineral extraction.